The lyrics were cynical and clever and angry and funny, but it was when we got back to the dorm and I put the record on that the true magic of Oingo Boingo became clear. The songs were bouncy and angular, and the band was improbably (and, for the time, uncooly) large, encompassing a full horn section in addition to the usual guitars-bass-keyboards-drums suspects. The music careened around, stopped on a dime, turned a sharp corner, and sped off down some other road only to quickly turn another sharp corner. It was quirky and engaging and impossible to predict, and it made me giggle to listen to. I loved it right away, but Eric and Allen were a little slower to recognize its charms. Eventually, thanks to my repeated playing of it, they became as big fans of that EP as I was, and we used to challenge each other to sing along to the whole record without missing a word – something we were all able to do before long.

Oingo Boingo quickly became one of my favorite bands, despite a mediocre first album. In fact, I liked them so much that they prompted me to go to my first concert. Growing up in rural Michigan, one didn’t get a lot of choices when it came to seeing rock concerts (Bob Seger, anybody?), but Oingo Boingo was on tour with the English Beat and The Police, and they were stopping at Pine Knob, a mere 50 or so miles from my house. My folks were kind enough to buy me tickets for my birthday, and on the appointed day, I borrowed my stepfather’s Duster, picked up Allen and a bag of weed, and set off for the show.

It’s really quite miraculous we survived the experience. The weed took longer to get than expected (as usual), and so we were running a little late when we finally hit the road. Halfway there, I thought I could shave a little time off the trip by passing a dozen cars in one go, until the camper at the head of the line suddenly turned left directly in front of me. Another half-hour of hell-bent driving, and we arrived at Pine Knob. I parked the car in some field and we ran in to take our seats in the outdoor auditorium. We were checking out the scene and smoking a joint when the announcer came on and said that, regrettably, Oingo Boingo would not be performing that night. I was crushed. But at least I was high and crushed and we stayed and saw the English Beat (pretty good), and The Police (excellent), and decided the evening was a success after all. Afterwards, we streamed out with the hoards and realized we hadn’t the faintest idea of where we were parked. There were thousands of cars in a dozen fields and, really, we could’ve been anywhere. Just as the enormity of how lost we were struck us, we walked directly into the back of the Duster. Divine providence was with us, a little karmic retribution for not getting to see Oingo Boingo, and, fortunately, stayed with us until we got home.

By the time we got out of the parking field, I realized how tired I was, so I enlisted Allen to help keep me awake on the hour drive home. He agreed and promptly passed out. I concentrated as hard as I could on driving the car and staying awake. And then I experienced one of the most frightening things I’ve ever endured. I woke up driving a car. I was so scared that I had fallen asleep and had so much adrenaline flowing through my veins that I was jolted wide awake. For about ten minutes. And then it happened again. Somehow, we managed to get home in one piece.

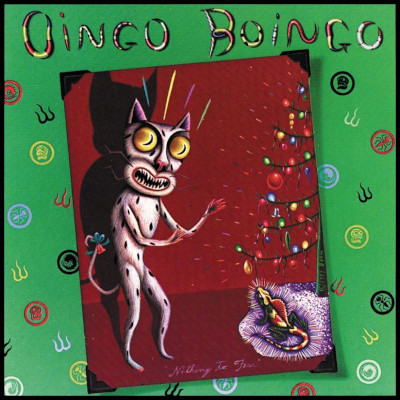

Oingo Boingo’s second album, Nothing to Fear, came out the following summer, and it is the title track from this album that I chose. Songwriter Danny Elfman was at his best when he was angry, and he got angry often – at everything from couch potatoes (Grey Matter) to bugs (Insects), to communists (Capitalism – with its great oft-repeated (among my friends) line, “when was the last time you dug a ditch, baby”), to more personal demons (Reptiles and Samurai). He’s also pretty mad about the notion that there’s “nothing to fear but fear itself”. From where he sits, there’s plenty to fear, and much of the song is a catalog of reasons to not be cheerful – from imminent nuclear devastation (“the Russian’s are about to pulverize us in our sleep tonight”), to child molesters (“won’t you make an old man happy, won’t you let me show you paradise, don’t ask your mother for advise”). Plus it has one of my all-time favorite bass lines propelling the song along.

Although Elfman’s songs are very smart and very quirky, they are helped immeasurably by guitarist Steve Bartek’s arrangements. It’s the multiple layers of sounds and textures playing against each other and the unusual scoring that really give these songs life. Plus, he’s a phenomenal (and wildly underrated) guitarist in his own rights, and can squeeze and cajole some wondrously weird sounds out of his axe.

Shortly after I moved to NYC, Oingo Boingo’s third, and best, album was released, the remarkable Good For Your Soul. Sporting the last of their series of truly hallucinogenic album covers, this disc unleashes the full force of Elfman’s anger and Bartek’s rarefied arranging skills on such barn-burners as Wake Up (It’s 1984) (and it was!), Good For Your Soul, and, especially, the momentous fever-dream, Sweat. It was while supporting this album that I finally got to see them live, and they were just like I thought they’d be. Danny Elfman was a seething psychopath, leaping around in front of the rest of band which looked like it included everything from math teachers to hitmen to the socially and mentally challenged.

The story is that founder Elfman hated rock music, preferring to spend his time listening to the glorious dissonance of Stravinsky (don’t knock that as an influence – notoriously oddball musician Frank Zappa used to listen to Edgard Varese as a teen and look how he turned out). Supposedly, The Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo, as they were once called, were originally a street theater troop and not a band. Tapped by his brother Richard to score his transplendantly surreal film, The Forbidden Zone, Danny recruited his fellow performers, gave them instruments, and Oingo Boingo the band was formed. It’s a good story, but I can’t believe it’s true. The musicianship is far too polished for that kind of random accident. Still, while they were on top of their game, there was nobody else like them. And then tragedy struck.

If, during the early ‘80s, I were to have made up a list of musicians that were the least likely to become top-tier film composers, I would have to admit that Danny Elfman would have appeared very near the top of that list. After all, there was nothing to indicate that his peculiar style of frenzied angular non-pop would be so well-suited for large orchestras. But it is. He wrote the score for Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, and was off and running. Now, he is perhaps better known as a composer than as the former leader of a new wave band. The tragedy is that he was so successful as a composer that he both had less time for the band, and, more importantly, less reason to be angry. Now, suddenly, with all that money and prestige, bugs and fear and couch potatoes and socialists didn’t seem so annoying. And with the loss of rage (or the softening of age), Elfman’s songs lost a lot of the bark and bite that made them so appealing. Good For Your Soul was the highest artistic point the band would hit, and from then on, success dragged each subsequent album further into the muck. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m glad someone like Elfman can be successful – it warms my heart to see such an obvious oddball do so well by straight society – I just wish it didn’t mean the tempering of the vision that made him such an interesting and entertaining oddball to begin with.