The first time I ever really took an interest in listening to the radio was during my first summer job, working the dish room in the girl’s cafeteria at Interlochen’s National Music Camp. It was strictly a peer pressure thing. I never really found popular popular music that enticing, but the radio was on all the time and all my friends listened, so I listened too. Each weekend, while slogging through the endless Sunday Brunch, we’d listen faithfully to Casey Kasem count down the American Top 40, each hoping our favorite tracks would rise a little more. Most of the music on the show was typically terrible (Rick Springfield, Kim Carnes, and The Oak Ridge Boys were making big runs at the time), but I was thrilled to discover a few songs that were seemingly too far outside the pop formula to make it into such hallowed ground. They were quirky, they relied heavily on synthesizers and, in retrospect, they were the harbingers of the new wave movement that would mark the one time in my life when what I liked was popular (and verse visa).

One of those delicious oddities was Lipps, Inc.’s only hit, the joyful, infectious Funkytown. Blondie was also wandering around the charts at the time with the nearly instrumental Atomic. But the song on the charts at that time that made me the most excited was Gary Numan’s Cars. Here was somebody who had completely forsaken the traditional centerpiece of popular music, the electric guitar, and had, instead, embraced the cold, clean world of synthesizers. And he made no attempt to make the synthesizers sound like anything other than fiercely artificial electronic tone generators and manipulators. The sounds were raw and harsh, the tune simplistic enough to sound like maybe it had been written by a machine, and the lyrics embraced alienation and isolation, wishing for a world in which the singer never had to leave the comfort and security of his car. And on top of all that, Gary Numan had somebody who actually played the viola in his band. The viola! The stringed albatross that hung around my neck, dooming me forever to thanklessly prop up the flashy violin or romantic cello, had actually shown up in a new wave band! I was hooked. My friends thought I was nuts as they breathlessly awaited the next playing of Bette Davis Eyes, but I could see a new day dawning and I couldn’t wait.

My two musical worlds were about to coalesce into one. Up until that point, I listened mostly to pure synthesizer music by such groundbreakers as Synergy, Tangerine Dream, Vangelis, Jean Michel Jarre, and Tomita (representing the US, Germany, Greece, France, and Japan, respectively). Most of this music was large and lush and almost symphonic in scope and downplayed the rhythmic elements to focus more on texture and timbre and the spacey sonics for which synthesizers were so well-suited. On the other hand, I also really appreciated the driving beat of rock songs, even though I wasn’t a big guitar hero and couldn’t really connect with the larger-than-life personas of rock stars. Gary Numan and Lipps Inc. and other groups that were starting to rumble around at that time showed that the hot energy of rock could be combined with the cool textures of synthesizers to a wonderful and surprisingly popular effect. I was ecstatic.

It has long been a curiosity of sorts that many British bands speak with heavy accents, but sing without them. The Beatles, for example, lose almost all of their Liverpudlian linguistics when they sing. Gary Numan, as I discovered when I bought The Pleasure Principle, did not. For whatever reason, he still sounds fiercely British when he sings, and it just helps add another layer of oddness to his songs – especially considering how poorly he sings. The Pleasure Principle, Gary’s third album and the one which spawned Cars, is not a great record. It’s sort of a one-note affair, but if you like that note, as I certainly did, than the album is a wonderful island on a sea of poopy pop pap.

The fact of the matter is, it’s very easy (and popular) to make fun of Gary Numan. But he turned out some wonderful – and surprisingly diverse – music during his (seemingly endless) career. Sure, he’d come out with a new version of Cars every few years, gussied up in the clothes of the moment, hoping to strike gold again, and that’s reason enough to make fun of him. But he was much more than a soulless machine licker. Each album has its sound, and each sound was different, but most people only heard Cars and just assumed that all of his stuff sounded like that. While he did tend to stick to synthesizers (and embarrassingly bad lyrics), he did release a now obscure record called Dance that was so mellow and ambient and undanceable (and which featured the trademark liquid fretless bass of Mick Karn) that it made my short list of best music to make out to (I’d usually put it on after Tina got tired of Roxy Music).

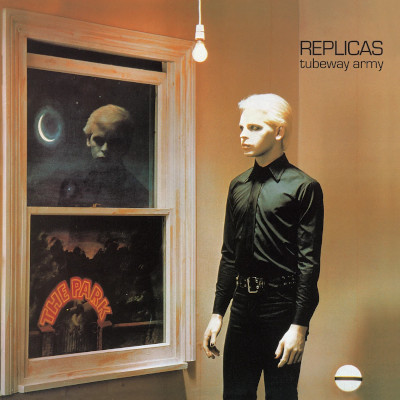

After that summer in the dish room, I moved into the dorm at Interlochen, and I brought my love of Gary Numan with me. By then, I had branched out a bit and bought Replicas, the album which preceded The Pleasure Principle. I was surprised to find Gary’s sonic palette a little richer on this album than on subsequent ones – he even makes frequent use of electric guitar, as can be heard on You Are In My Vision. Although, to his credit, it does sound like the guitar was played by a robot – and a particularly soulless one at that. The song is nothing spectacular – terrible lyrics badly sung to an irritatingly simplistic arrangement. And it does contain one of the worst meter fudges I’ve heard a singer make. Partway through, Gary sings “far too many people for a quite night with myself, oh, I could be anyone tonight”. The meter and rhythm of the song favor him accenting MYself instead of mySELF, but it’s a pretty minor thing. Far worse is the way he ends up singing “I could be aNYone tonight”. It’s so forced and disorienting that for a long time I thought he was singing “I could be a knee one tonight.” I figured it was some obscure British slang (“oi, he’s a really knee one, guv’nor”) or just another of Gary’s awkward images (“remember I was vapour”, "my mirrors tarnished with ‘no help’”, “we’re dreams in cold storage”, take your pick), until I realized it was just heroically bad phrasing.

The real reason this song has risen to the top of my Gary Numan pond is because one day, I was hanging out in the dorm with Eric and Allen while the record played. The chorus came around and, instead of hearing “you are in my vision, I can’t feel my face”, one of them thought he’d said “you are in my vision, you Godzilla face.” We immediately took off from there and changed the lyrics in the chorus to the most disgusting substitutes that we could think of, which in our case ended up being:

You are in my vision, you Godzilla face

You are in my vision, you anal slime

You are in my vision, you butt-fuck breath

and that is how I hear the song every time I play it. Which, admittedly, is not that often.

Years later, I found the ultimate greatest hits package which, surprisingly, fills out two entire CDs. While by no means essential listening for the laymen (Cars will do for most), it does have some interesting oddities. I was disappointed to see that he had included nothing from the Dance album (not even the glorious (but somewhat overinflated) Slowcar to China), but delighted to find a hidden bonus track of a frilly solo piano version of his classic Down in the Park track. There’s also what has to be the worst version of On Broadway ever recorded by anybody anywhere. In fact, it may be the worst cover version of anything ever.