Bobby McFerrin – Blackbird

Picking up right where I left off in high school, I found myself enamored of another beautiful and crazy dancer at Hampshire College. Kathy and I spent a little time together, but nothing ever developed from it. She was the third girl in my life that I asked out (one in junior high, one in high school, and one in college), and she was the third to shoot me down. Consequently, she became the last girl I ever asked out.

Feeling somewhat lost at school and unable to find my niche, I decided to visit the dance department and take a few classes. Even though it had been a couple of years since I had been a serious dancer, I still had enough muscle memory and tone to pick it up pretty quickly and I was soon noticed by the other dancers. One night, at an outdoor social dance, Kathy drunkenly asked me to be in a piece she was choreographing and, eager to apply myself to something I knew how to do and even more eager to get close to her, I agreed. After a couple of rehearsals, she came to my room to get some suggestions for interesting pieces of music that she might use. I gave her a few albums to listen to and promised to come to her room in a couple of nights to talk about it.

When I stopped by (teeth freshly brushed and hair all in place), she invited me in and had me make myself comfortable on her bed. We talked about some of the music I had brought and I agreed to make a mix of her favorite parts of two tracks, one by Mick Karn and the other by Orchestral Manouevers in the Dark. I had lent her my copy of OMD’s Architecture and Morality on the strict condition that she not use the title track, for that was the piece I had choreographed in high school. Of course, that was the piece she choose (being far and away the most interesting cut on the album) and I was powerless to resist her charms, so I agreed to work it into the mix.

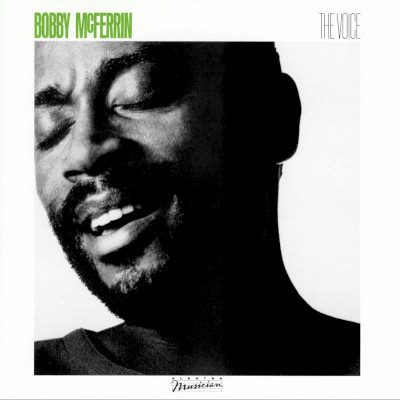

While we talked, she put on another album, one of her own, and I was absolutely transfixed. The album was called The Voice and it was by somebody I had never heard of, a jazz singer named Bobby McFerrin. It wasn’t surprising that I hadn’t heard of him because, first of all, jazz was not my thing, and second of all, this was well before Don’t Worry Be Happy became a huge hit and made McFerrin a household name. I always thought it was bitterly ironic that George Bush co-opted Don’t Worry Be Happy for his campaign (over McFerrin’s protests) because the message of the song is basically to ignore the fact that you’re broke and oppressed and miserable and have no future and to just turn that frown upside down and make lemonade out of life’s lemons. Perfect for Bush, who offered no hope, help, or solutions and just wanted everybody who wasn’t already rich and getting richer to shut the fuck up and be happy already.

McFerrin, who was a jazz pianist, says he heard a voice distinctly telling him to be a solo vocalist on July 11, 1977 (15 years to the day before I got married). Although he had no idea what it meant or how it was going to happen, six years later he found himself on stage alone for a two-hour concert, a concert that was completely improvised. This terrifying and exhilarating experience sealed his fate. His first album as a vocalist, The Voice, was recorded a few months later, on a solo tour through Europe, and remains one of the most stunning examples of vocal dexterity I have ever heard. Somehow, McFerrin manages to create an entire band with his voice, supplying rhythm and harmony to his melody and leaping all over the scale and stylistic map to create his one-of-a-kind vocal extravaganzas. There are several stunning songs on the album, including a rousing version of James Brown’s stirring I Feel Good, but by far my favorite track is his version of the Beatles’ immortal acoustic classic, Blackbird. McFerrin hiccups all over the scale in order to harmonize with himself. He sings while inhaling, whistles, slaps his chest, and imitates the flutter of the blackbird’s wings. And he ends the song with a wonderful imitation of an echo, spinning the song out into the void. It is a remarkable, breathtaking, incomprehensible performance, and I wouldn’t believe it was live if I didn’t hear the audience chuckling halfway through the song. But there’s another reason I like it so much.

When I was a kid, my dad’s favorite animal was the giraffe, and he had dozens of them around his house. But as he (and I) grew older, he switched to favoring the raven. The raven is an important bird in many cultures, being the bridge between the world of day and the world of night, between the heavens above and the earth below, or playing a crucial role in the creation of the world. For whatever reason, my father took a special shine to this great black bird, and it became his familiar during the last years of his life. He even named his last house Raven’s Way, a rustic wood cabin nestled deep in the woods near Kodiak, Alaska. It was from Raven’s Way that he trudged, during the inky black of an late November morning, to his office at the island’s mental health center, where he typed a last note before putting a gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger.

During the next week, while I was in Kodiak trying to tie up the loose ends of his life (a Sisyphean task if ever there was one), I became familiar with his familiar. On the last day, I sat in the rented car, waiting in a parking lot for a bank to open so I could do my last piece of official business before returning to the heat and light and life of LA. While sitting there, I suddenly realized that Blackbird was going through my head. As I became aware of the lyrics, I was stunned by how closely they related to my father’s life – almost as though it had been written with him in mind. Like the song’s namesake, my father was damaged goods, trying to make the best out of bad situation, trying to fly with broken wings, singing in the dead of night. Of course it wasn’t written for him, but I suppose everybody knows some blackbird, some tragic hero struggling against insurmountable odds and eventually succumbing to the inevitable. As I sat in the parking lot, numbly mouthing the words to the song, a giant raven landed on the hood of the car, directly in front of the windshield. I had never seen a bird land on an occupied car, and I was transfixed as the bird turned his head and met my eye (facing sideways, of course). We stared at each other for a breathless moment, and then he slowly turned away, walked to the edge of the hood, and flapped his powerful wings, which lifted him up and pushed him out over the bank, over the nearby docks, and out over the unforgiving ocean. I watched him turn into a dark speck and disappear, and the tears poured down my cheeks for the hundredth time that weekend. I couldn’t help but think of that bird as my father, coming to caw goodbye as he shuffled off his mortal coil.

All his life, he was only waiting for that moment to arrive.